Foto di Sebastião Salgado

L’onda della marea dei rifugiati, non un semplice passo di oche

selvatiche, gli occhi di carbone nei vagoni merci, le facce

smunte, e in particolare lo sguardo fisso dei bambini

emaciati, gli enormi fardelli che traversano i ponti, gli assali

che cricchiano con un suono di giunture e di ossa, la macchia scura

che passa le frontiere sulle carte geografiche e ne dissolve le forme,

come succede ai corpi dei morti dentro le fosse di calce, o come

fa il pacciame luccicante che si disfa sotto i piedi in autunno

nel fango, mentre il fumo di un cipresso segnala Sachenhausen,

e quelli che non stanno sopra un treno, che non hanno muli o cavalli,

quelli che hanno messo la sedia a dondolo e la macchina per cucire

sul carretto a mano perché da tempo le bestie hanno lasciato

i loro campi al galoppo per tornare alla mitologia del perdono,

alle campane di pietra sui ciottoli della domenica e al cono

della guglia del campanile aranciato che buca le nubi sopra i tigli,

quelli che appoggiano la mano stanca sulla sponda del carro

come sul fianco del mulo, le donne con la faccia di selce

e gli zigomi di vetro, con gli occhi velati di ghiaccio che hanno

il colore degli stagni dove posano le anitre, e per le quali

c’è un solo cielo e una sola stagione nel corso di un anno

ed è quando il corvo come un ombrello rotto sbatte le ali,

si sono tutti ridotti alla comune e incredibile lingua

della memoria, e questa gente che non ha una casa e nemmeno

una provincia parla delle fonti limpide e parla delle mele,

e del suono del latte in estate dentro le zangole piene,

e tu da dove vieni, da quale regione, io conosco

quel lago e anche le locande, la birra che si beve,

e quelle sono le montagne dove riponevo la mia fede,

ma adesso sulla carta, che è simile a un mostro, altro non si vede

che una rotta che ci porta verso il Nulla, anche se sul retro

c’è la veduta di un posto che si chiama la Valle del Perdono,

dove il solo governo è quello dell’albero dei pomi e le forze

schierate dell’esercito sono gli striscioni di orzo

all’interno di umili tenute, e questa è la visione

che a poco a poco si restringe dentro le pupille

di chi muore e di chi si abbandona in un fosso,

rigido e con la fronte che diventa fredda come le pietre

che ci hanno bucato le scarpe e grigia come le nuvole

che quando il sole si leva, si trasformano subito in cenere

sopra i pioppi e sopra le palme, nell’ingannevole aurora

di questo nuovo secolo che è il vostro.

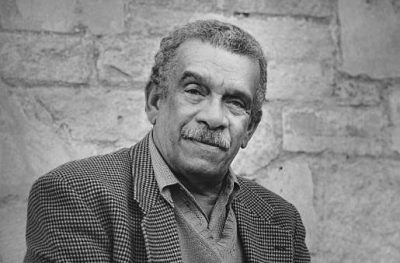

Derek Walcott

St. Lucia, Caraibi, 16 giugno 2000

(Traduzione di Luigi Sampietro)

dalla rivista “Poesia”, Anno XXIX, Ottobre 2016, N. 319, Crocetti Editore

∗∗∗

Prodigal, 3° excerpt

II

to Luigi Sampietro

The tidal motion of refugees, not the flight of wild geese,

the faces in freight cars, haggard and coal-eyed,

particularly the peaked stare of children,

the huge bundles crossing bridges, axles creaking

as if joints and bones were audible, the dark stain

spreading on maps whose shapes dissolve their frontiers

the way that corpses melt in a lime-pit or

the bright mulch of autumn is trampled into mud,

and the smoke of a cypress signals Sachsenhausen,

those without trains, without mules or horses,

those who have the rocking chair and the sewing machine

heaped on a human cart, a wagon without horses

for horses have long since galloped out of their field

back to the mythology of mercy, back to the cone

of the orange steeple piercing clouds over the lindens

and the stone bells of Sunday over the cobbles,

those who rest their hands on the sides of the carts

as if they were the flanks of mules, and the women

with flint faces, with glazed cheekbones, with eyes

the color of duck-ponds glazed over with ice,

for whom the year has only one season, one sky:

that of the rooks flapping like torn umbrellas,

all have been reduced into a common language,

the homeless, the province-less, to the incredible memory

of apples and clean streams, and the sound of milk

filling the summer churns, where are you from,

what was your district, I know that lake, I know the beer,

and its inns, I believed in its mountains,

now there is a monstrous map that is called Nowhere

and that is where we’re all headed, behind it

there is a view called the Province of Mercy,

where the only government is that of the apples

and the only army the wide banners of barley

and its farms are simple, and that is the vision

that narrows in the irises and the dying

and the tired whom we leave in ditches

before they stiffen and their brows go cold

as the stones that have broken our shoes,

as the clouds that grow ashen so quickly after dawn

over palm and poplar, in the deceitful sunrise

of this, your new century.

Derek Walcott

da “The Prodigal”, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2004