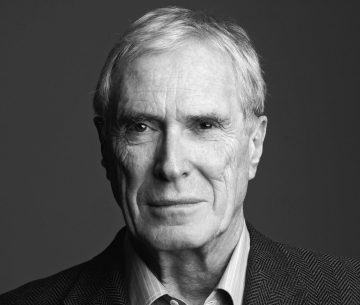

Foto di Julia Margaret Cameron

È una parola antica, che va sbiadendo.

Moltissimo volli.

Moltissimo pregai.

Io lo amai moltissimo.

Mi faccio strada camminando

con attenzione, per via delle ginocchia malandate

di cui mi frega assai meno

di quanto possiate immaginare

visto che esistono altre cose un pelino più importanti

(aspetta e vedrai).

Ho in mano un mezzo caffè

in una tazza di carta con

– me ne rammarico moltissimo –

un coperchio di plastica,

cerco di ricordare cos’erano quelle parole un tempo.

Moltissimo.

Com’era usata?

Moltissimo amati.

Moltissimo amati, siamo riuniti.

Moltissimo amati, siamo oggi qui riuniti

in questo album di foto dimenticate

che ho ritrovato di recente.

Sbiadite ormai,

color seppia, in bianco e nero, stampate a colori,

ognuno di noi così tanto più giovane.

Le Polaroid.

Cos’è una Polaroid? Chiede il neonato.

Neonato da un decennio.

Come spiegarlo?

Tu scatti e la foto esce dalla parte rialzata.

Alzata sopra cosa?

Con quello sguardo perplesso che vedo di continuo.

Così difficile da descrivere

i dettagli più minuti di come

– tutti questi moltissimo amati qui riuniti –

di come vivevamo un tempo.

Si incartava l’immondizia con la carta

del quotidiano legata con un filo.

Cos’è un quotidiano?

Voi capite cosa intendo.

Il filo però, di filo ne abbiamo ancora.

Lega le cose insieme.

Un filo di perle.

Ecco cosa ti dicono.

Come tenere traccia dei giorni?

Ognuno splendido, ognuno separato,

ognuno unico e finito.

Li ho tenuti sulla carta in un cassetto,

quei giorni, adesso svaniti.

Le perle possono essere usate per contare.

Come nei rosari.

Ma non mi piace avere pietre intorno al collo.

Lungo questa strada ci sono molti fiori,

sbiaditi adesso ché è agosto,

polverosi e diretti verso l’autunno.

Presto i crisantemi fioriranno,

i fiori dei morti, in Francia.

Non pensare che questo sia morboso.

Sono le cose come stanno.

Così difficile descrivere i dettagli più minuti dei fiori.

Ecco gli stami, niente a che fare con gli umani.

Ecco i pistilli, niente a che fare con le pistole.

Sono i dettagli più minuti a ostacolare i traduttori

e anche me, quando provo a descrivere.

Capite cosa intendo dire.

Tu puoi deviare. Tu puoi perderti.

Lo stesso accade alle parole.

Moltissimo amate, riunite qui insieme

in questo cassetto chiuso,

ormai sbiadite, mi mancate.

Mi manca chi è mancato, chi è partito troppo presto.

Mi mancano anche quelli che sono ancora qui.

Mi mancate tutti moltissimo.

Moltissimo rimpianto ho di voi.

Rimpianto: ecco un’altra parola

che non senti più tanto spesso.

Io rimpiango moltissimo.

Margaret Atwood

(Traduzione di Renata Morresi)

da “Moltissimo”, “Ponte alle Grazie”, 2021

∗∗∗

Dearly

It’s an old word, fading now.

Dearly did I wish.

Dearly did I long for.

I loved him dearly.

I make my way along the sidewalk

mindfully, because of my wrecked knees

about which I give less of a shit

than you may imagine

since there are other things, more important –

wait for it, you’ll see –

bearing half a coffee

in a paper cup with –

dearly do I regret it –

a plastic lid –

trying to remember what words once meant.

Dearly.

How was it used?

Dearly beloved.

Dearly beloved, we are gathered.

Dearly beloved, we are gathered here

in this forgotten photo album

I came across recently.

Fading now,

the sepias, the black and whites, the colour prints,

everyone so much younger.

The Polaroids.

What is a Polaroid? Asks the newborn.

Newborn a decade ago.

How to explain?

You took the picture and then it came out the top.

The top of what?

It’s that baffled look I see a lot.

So hard to describe

the smallest details of how –

all these dearly gathered together –

of how we used to live.

We wrapped up garbage

in newspaper tied with string.

What is newspaper?

You see what I mean.

String though, we still have string.

It ties things together.

A string of pearls.

That’s what they would say.

How to keep track of the days?

Each one shining, each one alone,

each one then gone.

I’ve kept some of them in a drawer on paper:

those days, fading now.

Beads can be used for counting.

As in rosaries.

But I don’t like stones around my neck.

Along this street there are many flowers,

fading now because it is August

and dusty, and heading into fall.

Soon the chrysanthemums will bloom,

flowers of the dead, in France.

Don’t think this is morbid.

It’s just reality.

So hard to describe the smallest details of flowers.

This is a stamen, nothing to do with men.

This is a pistil, nothing to do with guns.

It’s the smallest details that foil translators

and myself too, trying to describe.

See what I mean.

You can wander away. You can get lost.

Words can do that.

Dearly beloved, gathered here together,

in this closed drawer,

fading now, I miss you.

I miss the missing, those who left earlier.

I miss even those who are still here.

I miss you all dearly.

Dearly do I sorrow for you.

Sorrow: that’s another word

you don’t hear much any more.

I sorrow dearly.

Margaret Atwood

da “