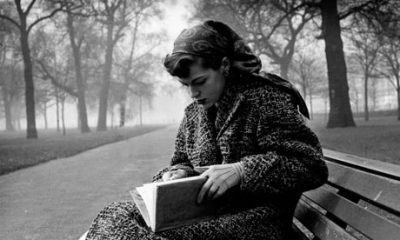

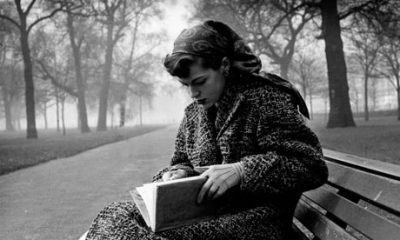

Foto di Bert Hardy

1.

Diverse settimane fa ho scoperto una fotografia di mia madre

seduta al sole, la sua faccia arrossata come per un successo o un trionfo.

Il sole splendeva. I cani

dormivano ai suoi piedi dove dormiva anche il tempo,

calmo e immobile come in ogni fotografia.

Ho spazzato via la polvere dal viso di mia madre.

La polvere, in effetti, copriva tutto; mi sembrava la foschia

persistente di nostalgia che protegge tutte le reliquie dell’infanzia.

Sullo sfondo, un assortimento di mobili da giardino, alberi e arbusti.

Il sole si spostava più in basso nel cielo, le ombre si allungavano e si oscuravano.

Più polvere ho rimosso, più queste ombre crescevano.

L’estate è arrivata. I bambini

si sporgevano oltre la siepe di rose, le loro ombre

si fondevano con le ombre delle rose.

Una parola mi è venuta in mente, riguardo

a questi spostamenti e cambiamenti, a queste cancellazioni

che adesso erano evidenti –

apparve e altrettanto rapidamente svanì.

Era cecità o oscurità, pericolo, confusione?

Arrivò l’estate, quindi l’autunno. Le foglie mutano

i bambini dei punti luminosi in una miscela di bronzo e terra di siena.

2.

Quando mi fui un po’ ripresa da questi eventi,

ho rimesso la fotografia come l’avevo trovata

tra le pagine di un antico libro rilegato,

molti suoi brani erano stati

annotati a margine, a volte con frasi ma più spesso

con vivaci domande ed esclamazioni

dal significato di “sono d’accordo” o “non sono sicuro, perplesso” —

L’inchiostro era sbiadito. In alcuni punti non capivo

quali pensieri fossero venuti in mente al lettore

ma attraverso le macchie potevo percepire

un senso di gravità, come se fossero cadute lacrime.

Ho tenuto il libro per un po’.

Era Morte a Venezia (in traduzione);

Avevo segnato la pagina nell’ipotesi in cui, come credeva Freud,

nulla accadesse per caso.

Così la piccola fotografia

è stata nuovamente sepolta, come il passato è sepolto nel futuro.

A margine c’erano due parole,

collegate da una freccia: “sterilità” e, in fondo alla pagina, “oblio” —

“E gli sembrava che il pallido e adorabile

Evocatore là fuori gli avesse sorriso e fatto cenno … “

3.

Com’è tranquillo il giardino;

nessuna brezza scuote la ciliegia del Corniolo.

L’estate è arrivata.

Com’è tranquillo

ora che la vita ha trionfato. I rozzi

pilastri dei sicomori

sostengono le mensole

immobili del fogliame,

il prato sottostante

lussureggiante, iridescente —

E in mezzo al cielo

il dio immodesto.

Le cose stanno, dice. Sono, non cambiano;

la risposta non cambia.

Com’è silenzioso il palcoscenico

come anche il pubblico; sembra

che respirare sia un’intrusione.

Deve essere molto vicino,

l’erba è senza ombre.

Com’è tranquillo, com’è silenzioso,

come un pomeriggio a Pompei.

4.

Madre morta la scorsa notte,

Madre che non muore mai.

L’inverno era nell’aria,

a molti mesi di distanza

ma comunque nell’aria.

Era il dieci di maggio.

Fiori di melo e giacinto

sbocciati nel giardino sul retro.

Potremmo sentire

Maria che canta canzoni dalla Cecoslovacchia —

Quanto sono sola –

canzoni di questo tipo.

Quanto sono sola

né madre, né padre –

il mio cervello sembra così vuoto senza di loro.

Gli aromi uscivano dalla terra;

i piatti erano nel lavandino,

risciacquati ma non in ordine.

Sotto la luna piena

Maria stava piegando la biancheria;

le lenzuola rigide erano diventate

rettangoli di luce lunare asciutti e bianchi.

Quanto sono sola, ma nella musica

la mia desolazione è la mia gioia.

Era il decimo giorno di maggio

come era stato il nono, l’ottavo.

La madre dormiva nel suo letto,

le braccia tese, la testa

in equilibrio tra di esse.

5.

Beatrice ha portato i bambini al parco di Cedarhurst.

Il sole splendeva. Aeroplani

passavano avanti e indietro, pacifici perché la guerra era finita.

Era il mondo della sua immaginazione:

vero e falso non aveva importanza.

Appena lucidato e scintillante —

quello era il mondo. La polvere

non era ancora precipitata sulla superficie delle cose.

Gli aerei passavano avanti e indietro, diretti

a Roma e Parigi — non potevi arrivarci

a meno che non sorvolassi il parco. Tutto

deve passare, niente può fermarsi —

I bambini si tenevano per mano, chinandosi

ad annusare le rose.

Erano cinque e sette.

Infinito, infinito: quella

era la sua percezione del tempo.

Si sedette su una panchina, un po’ nascosta dalle querce.

Lontano, la paura si avvicinò e se ne andò;

dalla stazione dei treni ne giungeva il suono.

Il cielo era rosa e arancione, più vecchio perché la giornata era finita.

Non c’era vento. Il giorno d’estate

proietta ombre a forma di quercia sull’erba verde.

Louise Glück

(TRADUZIONE DI MARCELLO COMITINI)

∗∗∗

A summer garden

1.

Several weeks ago I discovered a photograph of my mother

sitting in the sun, her face flushed as with achievement or triumph.

The sun was shining. The dogs

were sleeping at her feet where time was also sleeping,

calm and unmoving as in all photographs.

I wiped the dust from my mother’s face.

Indeed, dust covered everything; it seemed to me the persistent

haze of nostalgia that protects all relics of childhood.

In the background, an assortment of park furniture, trees, and shrubbery.

The sun moved lower in the sky, the shadows lengthened and darkened.

The more dust I removed, the more these shadows grew.

Summer arrived. The children

leaned over the rose border, their shadows

merging with the shadows of the roses.

A word came into my head, referring

to this shifting and changing, these erasures

that were now obvious —

it appeared, and as quickly vanished.

Was it blindness or darkness, peril, confusion?

Summer arrived, then autumn. The leaves turning,

the children bright spots in a mash of bronze and sienna.

2.

When I had recovered somewhat from these events,

I replaced the photograph as I had found it

between the pages of an ancient paperback,

many parts of which had been

annotated in the margins, sometimes in words but more often

in spirited questions and exclamations

meaning “I agree” or “I’m unsure, puzzled”—

The ink was faded. Here and there I couldn’t tell

what thoughts occurred to the reader

but through the blotches I could sense

urgency, as though tears had fallen.

I held the book awhile.

It was Death in Venice (in translation);

I had noted the page in case, as Freud believed,

nothing is an accident.

Thus the little photograph

was buried again, as the past is buried in the future.

In the margin there were two words,

linked by an arrow: “sterility” and, down the page, “oblivion”—

“And it seemed to him the pale and lovely

Summoner out there smiled at him and beckoned…”

3.

How quiet the garden is;

no breeze ruffles the Cornelian cherry.

Summer has come.

How quiet it is

now that life has triumphed. The rough

pillars of the sycamores

support the immobile

shelves of the foliage,

the lawn beneath

lush, iridescent—

And in the middle of the sky,

the immodest god.

Things are, he says. They are, they do not change;

response does not change.

How hushed it is, the stage

as well as the audience; it seems

breathing is an intrusion.

He must be very close,

the grass is shadowless.

How quiet it is, how silent,

like an afternoon in Pompeii.

4.

Mother died last night,

Mother who never dies.

Winter was in the air,

many months away

but in the air nevertheless.

It was the tenth of May.

Hyacinth and apple blossom

bloomed in the back garden.

We could hear

Maria singing songs from Czechoslovakia—

How alone I am—

songs of that kind.

How alone I am,

no mother, no father—

my brain seems so empty without them.

Aromas drifted out of the earth;

the dishes were in the sink,

rinsed but not stacked.

Under the full moon

Maria was folding the washing;

the stiff sheets became

dry white rectangles of moonlight.

How alone I am, but in music

my desolation is my rejoicing.

It was the tenth of May

as it had been the ninth, the eighth.

Mother slept in her bed,

her arms outstretched, her head

balanced between them.

5.

Beatrice took the children to the park in Cedarhurst.

The sun was shining. Airplanes

passed back and forth overhead, peaceful because the war was over.

It was the world of her imagination:

true and false were of no importance.

Freshly polished and glittering —

that was the world. Dust

had not yet erupted on the surface of things.

The planes passed back and forth, bound

for Rome and Paris — you couldn’t get there

unless you flew over the park. Everything

must pass through, nothing can stop—

The children held hands, leaning

to smell the roses.

They were five and seven.

Infinite, infinite—that

was her perception of time.

She sat on a bench, somewhat hidden by oak trees.

Far away, fear approached and departed;

from the train station came the sound it made.

The sky was pink and orange, older because the day was over.

There was no wind. The summer day

cast oak—shaped shadows on the green grass.

Louise Glück

da “Faithful and Virtuous Night”, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2014