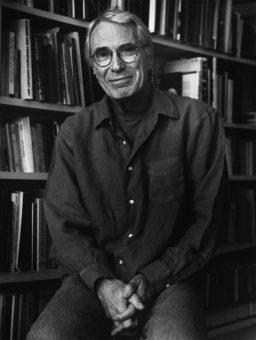

Mark Strand, photo di Chris Felver

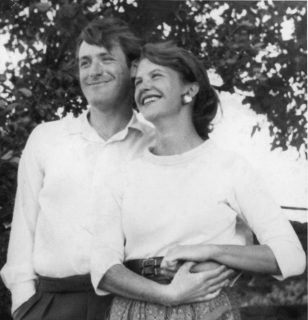

(Robert Strand 1908-1968)

1 IL CORPO VUOTO

Le mani erano tue, le braccia erano tue,

ma tu non c’eri.

Gli occhi erano tuoi, ma chiusi, e non si aprivano.

Il sole lontano c’era.

La luna sospesa sulla spalla bianca del colle c’era.

Il vento su Bedford Basin c’era.

La luce verde tenue dell’inverno c’era.

La tua bocca c’era,

ma tu non c’eri.

Quando qualcuno parlò, non vi fu risposta.

Nubi calarono

e seppellirono gli edifici sull’acqua,

e l’acqua fu muta.

I gabbiani guardavano.

Gli anni, le ore, che non t’avrebbero trovato

ruotavano ai polsi degli altri.

Non c’era dolore. Se n’era andato.

Non c’erano segreti. Non c’era nulla da dire.

L’ombra spargeva le sue ceneri.

II corpo era tuo, ma tu non c’eri.

L’aria rabbrividiva sulla sua pelle.

Il buio si chinava nei suoi occhi.

Ma tu non c’eri.

2 RISPOSTE

Perché viaggiavi?

Perché la casa era fredda.

Perché viaggiavi?

Perché è quel che ho sempre fatto fra tramonto e alba.

Cosa indossavi?

Indossavo un abito blu, camicia bianca, cravatta e calze gialle.

Cosa indossavi?

Non indossavo nulla. Mi riscaldava una sciarpa di pena.

Con chi dormivi?

Dormivo ogni notte con una donna diversa.

Con chi dormivi?

Dormivo solo. Ho sempre dormito solo.

Perché mi mentivi?

Ho sempre pensato di dire la verità.

Perché mi mentivi?

Perché la verità mente più di ogni altra cosa e io amo la verità.

Perché te ne vai?

Perché nulla ha senso per me ormai.

Perché te ne vai?

Non lo so. Non l’ho mai saputo.

Quanto dovrò aspettarti?

Non aspettarmi. Sono stanco e mi voglio sdraiare.

Sei stanco e ti vuoi sdraiare?

Sì, sono stanco e mi voglio sdraiare.

3 IL TUO MORIRE

Niente riusciva a fermarti.

Non il giorno più bello. Non la quiete. Non l’ondeggiare dell’oceano.

Continuavi a morire.

Non le piante

sotto cui camminavi, non le piante che ti davano ombra.

Non il dottore

che ti aveva avvertito, il dottorino biancocrinito che già una volta t’aveva salvato.

Continuavi a morire.

Niente riusciva a fermarti. Non tuo figlio. Non tua figlia

che ti imboccava e ti aveva reso di nuovo bambino.

Non tuo figlio che credeva saresti vissuto per sempre.

Non il vento che ti strattonava il bavero.

Non l’immobilità che si offriva al tuo movimento.

Non le scarpe che ti si appesantivano.

Non gli occhi che si rifiutavano di guardare avanti.

Niente riusciva a fermarti.

Te ne stavi in camera e guardavi la città

e continuavi a morire.

Andavi al lavoro e lasciavi che il freddo ti penetrasse i vestiti.

Lasciavi trasudare sangue nei calzini.

Il volto ti si faceva bianco.

La voce ti si spezzava in due.

Ti appoggiavi al bastone.

Ma niente riusciva a fermarti.

Non gli amici che ti consigliavano.

Non tuo figlio. Non tua figlia che ti guardava rimpicciolire.

Non la stanchezza che viveva nei tuoi sospiri.

Non i polmoni che si riempivano d’acqua.

Non le maniche che sopportavano il dolore delle braccia.

Niente riusciva a fermarti.

Continuavi a morire.

Quando giocavi con i bambini continuavi a morire.

Quando ti accomodavi a pranzo,

quando ti svegliavi la notte, bagnato di lacrime, il corpo scosso da singhiozzi,

continuavi a morire.

Niente riusciva a fermarti.

Non il passato.

Non il futuro con il suo bel tempo.

Non la vista dalla finestra, la vista del cimitero.

Non la città. Non la città orrenda dagli edifici di legno.

Non la sconfitta. Non il successo.

Non facevi altro che continuare a morire.

Avvicinavi l’orologio all’orecchio.

Ti sentivi venir meno.

Stavi a letto.

Ti mettevi a braccia conserte e sognavi il mondo senza te,

lo spazio sotto gli alberi,

lo spazio in camera tua,

gli spazi che si sarebbero fatti vuoti di te,

e continuavi a morire.

Niente riusciva a fermarti.

Non il tuo respiro. Non la tua vita.

Non la vita che volevi.

Non la vita che avevi.

Niente riusciva a fermarti.

4 LA TUA OMBRA

Hai la tua ombra.

I luoghi in cui sei stato l’hanno restituita.

I corridoi e i prati spogli dell’orfanotrofio l’hanno restituita.

La Newsboys Home l’ha restituita.

Le strade di New York l’hanno restituita e anche le strade di Montreal.

Le camere di Belém dove lucertole divoravano zanzare l’hanno restituita.

Le strade scure di Manaus e quelle afose di Rio l’hanno restituita.

Città del Messico dove te ne volevi andare l’ha restituita.

E Halifax dove il porto si lavava le mani di te l’ha restituita.

Hai la tua ombra.

Quando viaggiavi la scia bianca del tuo incedere affondava l’ombra, ma quando arrivavi la trovavi ad attenderti.

Avevi la tua ombra.

Le soglie che varcavi ti sottraevano l’ombra e quando uscivi te la restituivano. Avevi la tua ombra.

Anche quando te la dimenticavi, la ritrovavi; l’ombra era stata con te.

Una volta in campagna l’ombra di un albero coprì la tua ombra e tu non venisti riconosciuto.

Una volta in campagna pensasti che la tua ombra fosse proiettata da un altro. L’ombra non disse nulla.

I tuoi abiti portavano dentro la tua ombra; quando li toglievi, lei si diffondeva come il buio del tuo passato.

E le tue parole che volavano come foglie in un’aria persa, in un luogo che nessuno conosce, ti hanno restituito la tua ombra.

Gli amici ti hanno restituito la tua ombra.

I nemici ti hanno restituito la tua ombra. Hanno detto che era pesante e avrebbe coperto la tua tomba.

Quando moristi la tua ombra dormiva sulla bocca del forno e mangiò come pane le ceneri.

Esultava tra le rovine.

Vigilava mentre gli altri dormivano.

Risplendeva come cristallo tra le tombe.

Componeva se stessa come aria.

Voleva essere come neve sull’acqua.

Voleva non essere nulla, ma non era possibile.

Venne a casa mia.

Mi si sedette sulle spalle.

La tua ombra è tua. Glielo dissi. Le dissi che era tua.

L’ho portata con me troppo tempo. La restituisco.

5 LUTTO

Ti piangono.

Quando ti alzi a mezzanotte

e la rugiada luccica sulla pietra delle tue guance,

ti piangono.

Ti riconducono nella casa vuota.

Riportano dentro le sedie e i tavoli.

Ti fanno sedere e ti insegnano a respirare.

E il tuo respiro brucia,

brucia la scatola di pino e le ceneri cadono come luce del sole.

Ti danno un libro e ti dicono di leggere.

Ascoltano e gli occhi gli si colmano di lacrime.

Le donne ti carezzano le dita.

Ti pettinano restituendo il giallo ai tuoi capelli.

Radono via il gelo dalla tua barba.

Ti massaggiano le cosce.

Ti vestono elegante.

Ti strofinano le mani per tenerle calde.

Ti danno da mangiare. Ti offrono denaro.

Si inginocchiano e ti scongiurano di non morire.

Quando ti alzi a mezzanotte ti piangono.

Chiudono gli occhi e continuano a sussurrare il tuo nome.

Ma non possono sfilarti dalle vene la luce sepolta.

Non possono afferrare i tuoi sogni.

Vecchio mio, è impossibile.

Alzati e continua ad alzarti, non giova a nulla.

Ti piangono come possono.

6 L’ANNO NUOVO

È inverno, anno nuovo.

Nessuno ti conosce.

Via dalle stelle, dalla pioggia della luce,

giaci sotto il clima delle pietre.

Non c’è alcun filo che ti riconduca qui.

Gli amici s’assopiscono nel buio

del piacere e non possono ricordare.

Nessuno ti conosce. Sei il vicino del nulla.

Non vedi la pioggia e l’uomo che s’allontana a piedi,

il vento sudicio che soffia le proprie ceneri per la città.

Non vedi il sole che trascina la luna come un’eco.

Non vedi il cuore ferito andare in fiamme,

i crani degli innocenti farsi fumo.

Non vedi le cicatrici dell’abbondanza, gli occhi senza luce.

È finita. È inverno, anno nuovo.

I mansueti trascinano la propria pelle in paradiso.

I disperati soffrono il freddo con quelli che non hanno nulla da nascondere.

È finita e nessuno ti conosce.

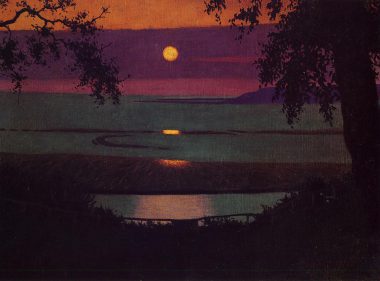

Luce di stella alla deriva su acqua nera.

Vi sono pietre nel mare che nessuno ha visto.

C’è una riva e la gente aspetta.

Perché è finita.

Perché c’è silenzio invece di un nome.

Perché è inverno, anno nuovo.

Mark Strand

(Traduzione di Damiano Abeni)

da “L’inizio di una sedia”, Donzelli Poesia, 1999

∗∗∗

Elegy for my father

(Robert Strand, 1908–68)

1 THE EMPTY BODY

The hands were yours, the arms were yours,

But you were not there.

The eyes were yours, but they were closed and would not open.

The distant sun was there.

The moon poised on the hill’s white shoulder was there.

The wind on Bedford Basin was there.

The pale green light of winter was there.

Your mouth was there,

But you were not there.

When somebody spoke, there was no answer.

Clouds came down

And buried the buildings along the water,

And the water was silent.

The gulls stared.

The years, the hours, that would not find you

Turned in the wrists of others.

There was no pain. It had gone.

There were no secrets. There was nothing to say.

The shade scattered its ashes.

The body was yours, but you were not there.

The air shivered against its skin.

The dark leaned into its eyes.

But you were not there.

2 ANSWERS

Why did you travel?

Because the house was cold.

Why did you travel?

Because it is what I have always done between sunset and sunrise.

What did you wear?

I wore a blue suit, a white shirt, yellow tie, and yellow socks.

What did you wear?

I wore nothing. A scarf of pain kept me warm.

Who did you sleep with?

I slept with a different woman each night.

Who did you sleep with?

I slept alone. I have always slept alone.

Why did you lie to me?

I always thought I told the truth.

Why did you lie to me?

Because the truth lies like nothing else and I love the truth.

Why are you going?

Because nothing means much to me anymore.

Why are you going?

I don’t know. I have never known.

How long shall I wait for you?

Do not wait for me. I am tired and I want to lie down.

Are you tired and do you want to lie down?

Yes, I am tired and I want to lie down.

3 YOUR DYING

Nothing could stop you.

Not the best day. Not the quiet. Not the ocean rocking.

You went on with your dying.

Not the trees

Under which you walked, not the trees that shaded you.

Not the doctor

Who warned you, the white-haired young doctor who saved you once.

You went on with your dying.

Nothing could stop you. Not your son. Not your daughter

Who fed you and made you into a child again.

Not your son who thought you would live forever.

Not the wind that shook your lapels.

Not the stillness that offered itself to your motion.

Not your shoes that grew heavier.

Not your eyes that refused to look ahead.

Nothing could stop you.

You sat in your room and stared at the city

And went on with your dying.

You went to work and let the cold enter your clothes.

You let blood seep into your socks.

Your face turned white.

Your voice cracked in two.

You leaned on your cane.

But nothing could stop you.

Not your friends who gave you advice.

Not your son. Not your daughter who watched you grow small.

Not fatigue that lived in your sighs.

Not your lungs that would fill with water.

Not your sleeves that carried the pain of your arms.

Nothing could stop you.

You went on with your dying.

When you played with children you went on with your dying.

When you sat down to eat,

When you woke up at night, wet with tears, your body sobbing,

You went on with your dying.

Nothing could stop you.

Not the past.

Not the future with its good weather.

Not the view from your window, the view of the graveyard.

Not the city. Not the terrible city with its wooden buildings.

Not defeat. Not success.

You did nothing but go on with your dying.

You put your watch to your ear.

You felt yourself slipping.

You lay on the bed.

You folded your arms over your chest and you dreamed of the world without you,

Of the space under the trees,

Of the space in your room,

Of the spaces that would now be empty of you,

And you went on with your dying.

Nothing could stop you.

Not your breathing. Not your life.

Not the life you wanted.

Not the life you had.

Nothing could stop you.

4 YOUR SHADOW

You have your shadow.

The places where you were have given it back.

The hallways and bare lawns of the orphanage have given it back.

The Newsboys’ Home has given it back.

The streets of New York have given it back and so have the streets of Montreal.

The rooms in Belém where lizards would snap at mosquitos have given it back.

The dark streets of Manaus and the damp streets of Rio have given it back.

Mexico City where you wanted to leave it has given it back.

And Halifax where the harbor would wash its hands of you has given it back.

You have your shadow.

When you traveled the white wake of your going sent your shadow below, but when you arrived it was there to greet you. You had your shadow.

The doorways you entered lifted your shadow from you and when you went out, gave it back. You had your shadow.

Even when you forgot your shadow, you found it again; it had been with you.

Once in the country the shade of a tree covered your shadow and you were not known.

Once in the country you thought your shadow had been cast by somebody else. Your shadow said nothing.

Your clothes carried your shadow inside; when you took them off, it spread like the dark of your past.

And your words that float like leaves in an air that is lost, in a place no one knows, gave you back your shadow.

Your friends gave you back your shadow.

Your enemies gave you back your shadow. They said it was heavy and would cover your grave.

When you died your shadow slept at the mouth of the furnace and ate ashes for bread.

It rejoiced among ruins.

It watched while others slept.

It shone like crystal among the tombs.

It composed itself like air.

It wanted to be like snow on water.

It wanted to be nothing, but that was not possible.

It came to my house.

It sat on my shoulders.

Your shadow is yours. I told it so. I said it was yours.

I have carried it with me too long. I give it back.

5 MOURNING

They mourn for you.

When you rise at midnight,

And the dew glitters on the stone of your cheeks,

They mourn for you.

They lead you back into the empty house.

They carry the chairs and tables inside.

They sit you down and teach you to breathe.

And your breath burns,

It burns the pine box and the ashes fall like sunlight.

They give you a book and tell you to read.

They listen and their eyes fill with tears.

The women stroke your fingers.

They comb the yellow back into your hair.

They shave the frost from your beard.

They knead your thighs.

They dress you in fine clothes.

They rub your hands to keep them warm.

They feed you. They offer you money.

They get on their knees and beg you not to die.

When you rise at midnight they mourn for you.

They close their eyes and whisper your name over and over.

But they cannot drag the buried light from your veins.

They cannot reach your dreams.

Old man, there is no way.

Rise and keep rising, it does no good.

They mourn for you the way they can.

6 THE NEW YEAR

It is winter and the new year.

Nobody knows you.

Away from the stars, from the rain of light,

You lie under the weather of stones.

There is no thread to lead you back.

Your friends doze in the dark

Of pleasure and cannot remember.

Nobody knows you. You are the neighbor of nothing.

You do not see the rain falling and the man walking away,

The soiled wind blowing its ashes across the city.

You do not see the sun dragging the moon like an echo.

You do not see the bruised heart go up in flames,

The skulls of the innocent turn into smoke.

You do not see the scars of plenty, the eyes without light.

It is over. It is winter and the new year.

The meek are hauling their skins into heaven.

The hopeless are suffering the cold with those who have nothing to hide.

It is over and nobody knows you.

There is starlight drifting on the black water.

There are stones in the sea no one has seen.

There is a shore and people are waiting.

And nothing comes back.

Because it is over.

Because there is silence instead of a name.

Because it is winter and the new year.

Mark Strand

da “The Story of Our Lives”, Atheneum, 1973