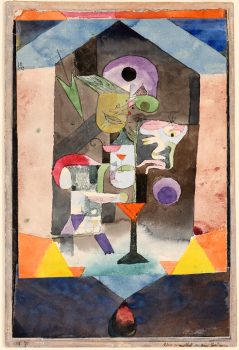

Félix Vallotton, The Wind, 1910, The National Gallery of Art, Washington

Il cielo sembrava così piccolo quel giorno d’inverno,

Una luce sporca su un mondo smorto,

Contratto come uno stecco raggrinzito.

Non era l’ombra di nube e freddo,

Ma un senso della distanza del sole:

L’ombra di un senso suo proprio.

Una consapevolezza che il giorno concreto

Era tanto meno. Solo il vento

Sembrava grande, sonoro, alto, forte.

E mentre pensava dentro il pensiero

Del vento, ignorando che quel pensiero

Non era né suo né di un altro qualunque,

L’immagine appropriata di sé,

Così formata, divenne lui: respirò

Il respiro di un’altra natura come suo,

Solo un respiro momentaneo,

Fuori e oltre la luce sporca

Che mai avrebbe potuto essere animale,

Una natura ancora priva di forma,

Fuorché quella di lui – forse quella di lui

Nell’ozio violento della domenica.

Wallace Stevens

(Traduzione di Massimo Bacigalupo)

da “Il mondo come meditazione”, Guanda, 2010

∗∗∗

The Constant Disquisition of the Wind

The sky seemed so small that winter day,

A dirty light on a lifeless world,

Contracted like a withered stick

It was not the shadow of cloud and cold,

But a sense of the distance of the sun —

The shadow of a sense of his own,

A knowledge that the actual day

Was so much less. Only the wind

Seemed large and loud and high and strong.

And as he thought within the thought

Of the wind, not knowing that that thought

Was not his thought, nor anyone’s,

The appropriate image of himself,

So formed, became himself and he breathed

The breath of another nature as his own,

But only its momentary breath,

Outside of and beyond the dirty light,

That never could be animal,

A nature still without a shape,

Except his own — perhaps, his own

In a Sunday’s violent idleness.

Wallace Stevens

da “The Collected Poems of Wallace Stevens”, Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 1971