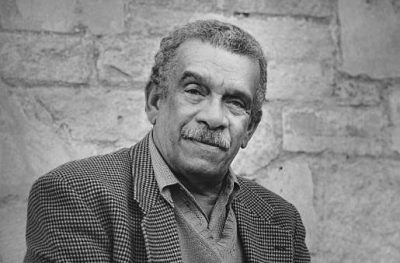

Foto di Mimmo Jodice

Dove sono i vostri monumenti, le vostre battaglie, màrtiri?

Dov’è la vostra memoria tribale? Signori,

in quella grigia volta. Il mare. Il mare

li rinchiude. Il mare è Storia.

All’inizio ribolliva l’olio,

pesante come il caos;

poi, come una luce in fondo a una galleria,

la lanterna d’una caravella,

e quella fu la Genesi.

Poi ci furono gli urli assordanti,

la merda, i lamenti:

l’Esodo.

Osso ad osso saldato dal corallo,

mosaici

avvolti dall’ombra benedicente dello squalo,

quella fu l’Arca della Testimonianza.

Poi vennero dai pizzicati fili

della luce sul fondo del mare

l’arpe dolenti della cattività babilonese,

quali le bianche cipree agglomerate come manette

sulle donne annegate,

e quelli furono gli eburnei bracciali

del Canto di Salomone,

ma il mare continuava a voltare pagine bianche

cercando la Storia.

Poi vennero gli uomini con occhi pesanti come ancore

che affondavano senza tombe,

briganti che grigliavano bestiame,

lasciando le loro costole carbonizzate come foglie di palma sul lido,

poi lo schiumoso, feroce gabbiano

della marea che ingoia Port Royal,

e quello fu Giona,

ma dov’è il vostro Rinascimento?

Signore, è chiuso in quelle sabbie

laggiù oltre il fiacco piano del frangente,

dove gli uomini di guerra scendevano;

metti gli occhiali subacquei, ti ci porterò io,

È tutto impalpabile e glauco

tra i colonnati di corallo,

oltre le finestre gotiche delle gorgonie

fin dove la crostosa cernia, occhivenata,

ammicca, carica dei suoi gioielli, come una calva regina;

e queste grotte lunettate con cirripedi

bucherellati come pietra

sono le nostre cattedrali,

e la fornace prima degli uragani:

Gomorra. Ossa tritate dai mulini a vento

in marna e crusca −

ecco le Lamentazioni −

nient’altro che Lamentazioni,

non Storia;

poi vennero, come schiuma sul labbro semiasciutto del fiume,

le brune canne dei villaggi

che spumeggiano e congelano in città,

e la sera, i cori dei moscerini,

e, sopra, le cuspidi

spinte nel fianco di Dio

mentre Suo figlio moriva, e quello fu il Nuovo Testamento.

Poi vennero le bianche sorelle che applaudivano

il progresso dell’onda,

ed ecco l’Emancipazione −

giubilo, giubilo −

presto svanito

mentre il pizzo del mare s’asciugava al sole,

ma non era la Storia,

non era che fede,

e poi ogni roccia divenne nazione a sé;

poi venne il sinodo delle mosche,

poi venne l’airone segretariale,

poi venne la rumorosa rana toro in cerca di voti,

lucciole con idee brillanti

e pipistrelli come ambasciatori volanti

e la mantide, come una poliziotta in cachi,

e i pelosi bruchi dei giudici

che esaminavano ogni caso da vicino,

e poi nelle scure orecchie delle felci

e nel gorgoglio salino delle rocce

con i loro stagni di mare ecco il suono

come un sussurro senza alcun’ eco

della Storia, che incomincia.

Derek Walcott

(Traduzione di Nicola Gardini)

dalla rivista “Poesia”, Anno XVIII, Dicembre 2005, N. 200, Crocetti Editore

∗∗∗

The sea is History

Where are your monuments, your battles, martyrs?

Where is your tribal memory? Sirs,

in that gray vault. The sea. The sea

has locked them up. The sea is History.

First, there was the heaving oil,

heavy as chaos;

then, like a light at the end of a tunnel,

the lantern of a caravel,

and that was Genesis.

Then there were the packed cries,

the shit, the moaning:

Exodus.

Bone soldered by coral to bone,

mosaics

mantled by the benediction of the shark’s shadow,

that was the Ark of the Covenant.

Then came from the plucked wires

of sunlight on the sea floor

the plangent harps of the Babylonian bondage,

as the white cowries clustered like manacles

on the drowned women,

and those were the ivory bracelets

of the Song of Solomon,

but the ocean kept turning blank pages

looking for History.

Then came the men with eyes heavy as anchors

who sank without tombs,

brigands who barbecued cattle,

leaving their charred ribs like palm leaves on the shore,

then the foaming, rabid maw

of the tidal wave swallowing Port Royal,

and that was Jonah,

but where is your Renaissance?

Sir, it is locked in them sea sands

out there past the reef’s moiling shelf,

where the men-o’-war floated down;

strop on these goggles, I’ll guide you there myself.

It’s all subtle and submarine,

through colonnades of coral,

past the gothic windows of sea fans

to where the crusty grouper, onyx-eyed,

blinks, weighted by its jewels, like a bald queen;

and these groined caves with barnacles

pitted like stone

are our cathedrals,

and the furnace before the hurricanes:

Gomorrah. Bones ground by windmills

into marl and cornmeal,

and that was Lamentations—

that was just Lamentations,

it was not History;

then came, like scum on the river’s drying lip,

the brown reeds of villages

mantling and congealing into towns,

and at evening, the midges’ choirs,

and above them, the spires

lancing the side of God

as His son set, and that was the New Testament.

Then came the white sisters clapping

to the waves’ progress,

and that was Emancipation—

jubilation, O jubilation—

vanishing swiftly

as the sea’s lace dries in the sun,

but that was not History,

that was only faith,

and then each rock broke into its own nation;

then came the synod of flies,

then came the secretarial heron,

then came the bullfrog bellowing for a vote,

fireflies with bright ideas

and bats like jetting ambassadors

and the mantis, like khaki police,

and the furred caterpillars of judges

examining each case closely,

and then in the dark ears of ferns

and in the salt chuckle of rocks

with their sea pools, there was the sound

like a rumor without any echo

of History, really beginning.

Derek Walcott

da “The Star-Apple Kingdom”, New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1979