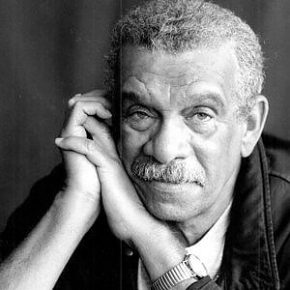

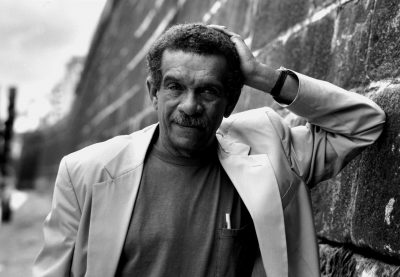

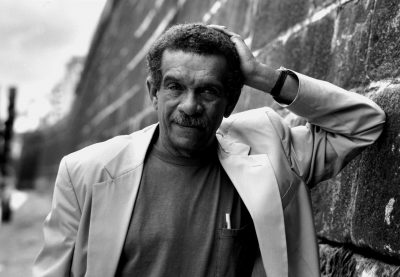

Derek Walcott

per Joseph Brodsky

I

Sulla chiara strada per Roma, oltre Mantova,

c’erano steli di riso, e ho udito, nell’eccitazione del vento,

i bruni cani del latino ansimare accanto alla macchina,

le loro ombre sfrecciavano sul ciglio in traduzione scorrevole,

oltre campi cintati da pioppi, cascine in pietra,

sostantivi da un testo di scuola, Orazio, Virgilio;

frasi di Ovidio passavano in verdi sbavature,

dirette verso prospettive di busti senza nasi,

rovine a bocca aperta e corridoi senza tetto

di Cesari il cui secondo mantello è ora fatto di polvere,

e questa voce che fruscia tra le canne è la tua.

Per ogni verso c’è un tempo e una stagione.

Tu hai ravvivato forme e strofe; questi campi rasati sono

la tua barba incolta che mi graffia la guancia alla partenza,

iridi grigie, le stoppie di grano dei tuoi capelli in aria.

Dimmi che non sei svanito, che sei sempre in Italia.

Sì. Per sempre. Dio. Per sempre immobile e muto come i campi

lombardi, come i bianchi vuoti di quella prigione,

pagine cancellate da un regime. E anche se il suo paesaggio lenisce

l’esilio tuo e di Nasone, la poesia è sempre tradimento

perché è verità. I tuoi pioppi vorticano nel sole.

II

Frullo d’ali di piccione fuori da una finestra di legno,

il fremito di un’anima agile che lascia il cuore consunto.

Il sole tocca i campanili. Clangore del Cinquecento,

nello schiaffo dell’onda attraccano e ripartono vaporetti,

lasciando l’ombra del viaggiatore sulla scena ondeggiante

a guardare il luccichio creato dal traghetto, come un pettine

tra capelli biondi che s’intrecciano al suo passaggio,

o copertine che racchiudono la schiuma dell’ultima pagina,

o qualunque sia il biancore che m’acceca coi suoi fiocchi

cancellando pini e conifere. Joseph, perché scrivo questo

se tu non puoi leggerlo? Le finestre del dorso di un libro

si aprono su un chiostro dove ogni cupola è un pretesto

per la tua anima, che come un piccione d’ardesia si libra

sull’acqua coniata e la luce ferisce come pioggia. Domenica.

I rintocchi dissennati dei campanili sono per te, che sapevi

come questa città dalle trine di pietra guarisca le nostre colpe,

simile al leone che con la zampa di ferro impedisce all’orbe

di rotolare sotto ali guardiane. Barche dal collo di violino

e ragazze dal collo di gondola erano la tua giurisdizione.

Com’è predestinato, il giorno del tuo compleanno, parlare di te a Venezia.

In questi giorni, nelle librerie, devio verso le biografie,

e la mia mano plana sui nomi con artigli aperti da piccione.

Sul mare, oltre la laguna, si chiudono parentesi

di cupole. Scesa dal traghetto, la tua ombra volta gli angoli

di un libro, si ferma in fondo a una prospettiva, e mi attende.

III

In questo paesaggio di vigne e colline hai portato un tema

che si muove fra le tue strofe inclinate, fa trasudare gli acini

e offusca le province: il lento inno nordico

della nebbia, la terra senza confini, nubi le cui forme

mutano con rabbia quando iniziamo ad associarle

a echi concreti, brecce dove l’eternità si spalanca

in una porticina azzurra. Ogni cosa solida le attende,

l’albero che diventa legna, la legna fumo del focolare,

la colomba l’eco del volo, la rima la sua eco, il tratto

dell’orizzonte che svanisce, il lavoro dei rametti

sulla pagina bianca e ciò che ricopre il loro cirillico: la neve,

il campo bianco che un corvo attraversa col suo gracchio nero,

sono una geografia distante, e non solo ora,

sei sempre stato là, la nebbia che con la zampa flessuosa

oscura il globo: sei sempre stato più felice

tra i margini freddi e incerti, non nel sole accecante

sull’acqua, in questo traghetto che si accosta alla banchina

quando un viaggiatore spegne l’ultima scintilla di una sigaretta

sotto il tacco, e il suo volto amato svanisce

in una moneta che le dita della nebbia strofinano.

IV

La schiuma al largo dello stretto mormora Montale

in sale grigio, un mare ardesia, e oltre, colline maculate

d’indaco e lilla, poi la vista dei cactus in Italia

e le palme, nomi che scintillano sull’orlo del Tirreno.

La tua eco arriva tra gli scogli, ridacchiando tra le rime

quando l’onda si frange ed è svanita per sempre!

Questi versi gettati per pesci arcobaleno o una retata di spratti,

pesci pappagallo, argentine, ballerini scarlatti,

e l’odore rancido e universale della poesia, un mare cobalto

e le palme all’aeroporto che si sorprendono da sole; ne sento l’odore,

alghe come capelli che fluttuano nell’acqua, la mica in Sicilia,

un odore più antico e più fresco delle cattedrali normanne

o degli acquedotti restaurati, le mani ruvide dei pescatori

la loro àncora di dialetti, e frasi che si seccano su muri

eretti nel muschio. Queste le sue origini, la poesia,

restano nei versi ripetuti delle onde e le loro creste,

remi e scansione, gli stormi e un unico orizzonte, chiglie

incuneate nella sabbia, la tua isola, o i versi di Montale

o Quasimodo che si dibattono come anguille in una cesta.

Sto scendendo al margine della secca per ricominciare,

Joseph, con un primo verso, una vecchia rete,

la stessa sollecitudine. Studierò l’orizzonte che si schiude,

la scansione dei colpi della pioggia, per dissolvermi

in un racconto più grande delle nostre vite, del mare, del sole.

V

Il mio colonnato di cedri fra le cui arcate l’oceano

sussurra il suo messale, ogni tronco una lettera

miniata come un breviario con frutti e viti,

lungo il quale sento l’eco incessante di un’architettura

di stanze col profilo di San Pietroburgo, i versi

di un cantore amplificato, la devozione della sua tonsura.

La prosa è lo scudiero della condotta, la poesia il cavaliere

che infilza il drago fiammeggiante con la lancia della penna,

è quasi disarcionato come un picador, ma si drizza in sella.

Accucciata sopra un foglio con la stessa postura,

una nube ripete nella sua forma il diradarsi dei tuoi capelli.

Un metro e un contegno modellati su quelli di Wystan,

strofe dal profilo romano e aperto, il busto di un Cesare minore

che allo strepito dell’arena preferisce una provincia distante,

un dovere che la polvere oscura. Sono innalzato sopra

il messale dell’onda, le colonne dei cedri, per guardare dall’alto

la cifra del mio dolore, la tua lapide, sono andato alla deriva

sopra libri di cimiteri verso un Atlantico le cui rive

si riducono, sono un’aquila che ti riporta in Russia,

stringendo fra gli artigli la ghianda del tuo cuore che ti rende,

oltre il Mar Nero di Publio Nasone, alle radici di un faggio.

Sono innalzato dal dolore e dall’elogio, così che

la tua macchia si dilati per l’esultanza, un punto che ascende.

VI

Ora, sera dopo sera dopo sera,

agosto fruscerà dalle conifere, una luce arancio

s’infiltrerà tra le pietre della strada, ombre

giacciono parallele come remi sul lungo scafo d’asfalto,

cavalli strigliati scuotono le teste in campi aridi

e la prosa esita sul ciglio del metro. La volta

si amplia, il soffitto attraversato da pipistrelli o rondini,

il cuore scala colline lilla nella luce che declina

e la grazia offusca gli occhi di un uomo che si avvicina

alla sua casa. Gli alberi serrano le porte, le onde

chiedono ascolto. La sera è un’incisione, il medaglione

di una sagoma rabbuia coloro che amiamo nel loro profilo, come il tuo,

la cui poesia trasforma il lettore in poeta. Il leone

del promontorio si trasforma come quello di San Marco, metafore

si riproducono e svolazzano nella caverna della mente,

e si sente nell’incantesimo dell’onda e nelle conifere dell’agosto,

e si legge il cirillico delle fronde che gesticolano mentre

il silenzioso consiglio dei cumuli inizia a radunarsi

su un Atlantico dalla luce calma quanto quella di uno stagno,

i lampioni spuntano come frutti nel villaggio, sopra i tetti,

e l’alveare delle costellazioni appare, sera dopo sera,

la tua voce, tra scure canne di versi che risplendono di vita.

Derek Walcott

(Traduzione di Matteo Campagnoli)

da “Prima luce”, in “Derek Walcott, Isole”, Poesie scelte (1948-2004), Adelphi, 2009

∗∗∗

31. Italian eclogues

for Joseph Brodsky

I

On the bright road to Rome, beyond Mantua,

there were reeds of rice, and I heard, in the wind’s elation,

the brown dogs of Latin panting alongside the car,

their shadows sliding on the verge in smooth translation,

past fields fenced by poplars, stone farms in character,

nouns from a schoolboy’s text, Vergilian, Horatian,

phrases from Ovid passing in a green blur,

heading towards perspectives of noseless busts,

open-mouthed ruins and roofless corridors

of Caesars whose second mantle is now the dust’s,

and this voice that rustles out of the reeds is yours.

To every line there is a time and a season.

You refreshed forms and stanzas; these cropped fields are

your stubble grating my cheeks with departure,

gray irises, your corn-wisps of hair blowing away.

Say you haven’t vanished, you’re still in Italy.

Yeah. Very still. God. Still as the turning fields

of Lombardy, still as the white wastes of that prison

like pages erased by a regime. Though his landscape heals

the exile you shared with Naso, poetry is still treason

because it is truth. Your poplars spin in the sun.

II

Whir of a pigeon’s wings outside a wooden window,

the flutter of a fresh soul discarding the exhausted heart.

Sun touches the bell-towers. Clangor of the cinquecento,

at wave-slapped landings vaporettos warp and depart

leaving the traveller’s shadow on the swaying stage

who looks at the glints of water that his ferry makes

like a comb through blond hair that plaits after its passage,

or book covers enclosing the foam of their final page,

or whatever the whiteness that blinds me with its flakes

erasing pines and conifers. Joseph, why am I writing this

when you cannot read it? The windows of a book spine open

on a courtyard where every cupola is a practice

for your soul encircling the coined water of Venice

like a slate pigeon and the light hurts like rain.

Sunday. The bells of the campaniles’ deranged tolling

for you who felt this stone-laced city healed our sins,

like the lion whose iron paw keeps our orb from rolling

under guardian wings. Craft with the necks of violins

and girls with the necks of gondolas were your province.

How ordained, on your birthday, to talk of you to Venice.

These days, in bookstores I drift towards Biography,

my hand gliding over names with a pigeon’s opening claws.

The cupolas enclose their parentheses over the sea

beyond the lagoon. Off the ferry, your shade turns the corners

of a book and stands at the end of perspective, waiting for me.

III

In this landscape of vines and hills you carried a theme

that travels across your raked stanzas, sweating the grapes

and blurring their provinces: the slow northern anthem

of fog, the country without borders, clouds whose shapes

change angrily when we begin to associate them

with substantial echoes, holes where eternity gapes

in a small blue door. All solid things await them,

the tree into kindling, the kindling to hearth-smoke,

the dove in the echo of its flight, the rhyme its echo,

the horizon’s hyphen that fades, the twigs’ handiwork

on a blank page and what smothers their cyrillics: snow,

the white field that a raven crosses with its black caw,

they are a distant geography and not only now,

you were always in them, the fog whose pliant paw

obscures the globe; you were always happier

with the cold and uncertain edges, not blinding sunlight

on water, in this ferry sidling up to the pier

when a traveller puts out the last spark of a cigarette

under his heel, and whose loved face will disappear

into a coin that the fog’s fingers rub together.

IV

The foam out on the sparkling strait muttering Montale

in gray salt, a slate sea, and beyond it flecked lilac

and indigo hills, then the sight of cactus in Italy

and palms, names glittering on the edge of the Tyrrhenian.

Your echo comes between the rocks, chuckling in fissures

when the high surf vanishes and is never seen again!

These lines flung for sprats or a catch of rainbow fishes,

the scarlet snapper, the parrot fish, argentine mullet,

and the universal rank smell of poetry, cobalt sea,

and self-surprised palms at the airport; I smell it,

weeds like hair swaying in water, mica in Sicily,

a smell older and fresher than the Norman cathedrals,

or restored aqueducts, the raw hands of fishermen

their anchor of dialect, and phrases drying on walls

based in moss. These are its origins, verse, they remain

with the repeated lines of waves and their crests, oars

and scansion, flocks and one horizon, boats with keels

wedged into sand, your own island or Quasimodo’s

or Montale’s lines wriggling like a basket of eels.

I am going down to the shallow edge to begin again,

Joseph, with a first line, with an old net, the same expedition.

I will study the opening horizon, the scansion’s strokes of the rain,

to dissolve in a fiction greater than our lives, the sea, the sun.

V

My colonnade of cedars between whose arches the ocean

drones the pages of its missal, each trunk a letter

embroidered like a breviary with fruits and vines,

down which I continue to hear an echoing architecture

of stanzas with St. Petersburg’s profile, the lines

of an amplified cantor, his tonsured devotion.

Prose is the squire of conduct, poetry the knight

who leans into the flaming dragon with a pen’s lance,

is almost unhorsed like a picador, but tilts straight

in the saddle. Crouched over paper with the same stance,

a cloud in its conduct repeats your hair-thinning shape.

A conduct whose meter and poise were modeled on Wystan’s,

a poetry whose profile was Roman and open, the bust

of a minor Caesar preferring a province of distance

to the roar of arenas, a duty obscured by dust.

I am lifted above the surf’s missal, the columned cedars,

to look down on my digit of sorrow, your stone, I have drifted

over books of cemeteries to the Atlantic whose shores

shrivel, I am an eagle bearing you towards Russia,

holding in my claws the acorn of your heart that restores

you past the Black Sea of Publius Naso

to the roots of a beech-tree; I am lifted with grief and praise, so

that your speck widens with elation, a dot that soars.

VI

Now evening after evening after evening,

August will rustle from the conifers, an orange light

will seep through the stones of the causeway, shadows

lie parallel as oars across the long hull of asphalt,

the heads of burnished horses shake in parched meadows

and prose hesitates on the verge of meter. The vault

increases, its ceiling crossed by bats or swallows,

the heart climbs lilac hills in the light’s declension,

and grace dims the eyes of a man nearing his own house.

The trees close their doors, and the surf demands attention.

Evening is an engraving, a silhouette’s medallion

darkens loved ones in their profile, like yours,

whose poetry transforms reader into poet. The lion

of the headland darkens like St. Mark’s, metaphors

breed and flit in the cave of the mind, and one hears

in the waves’ incantation and the August conifers,

and reads the ornate cyrillics of gesturing fronds

as the silent council of cumuli begins convening

over an Atlantic whose light is as calm as a pond’s

and lamps bud like fruit in the village, above roofs, and the hive

of constellations appears, evening after evening,

your voice, through the dark reeds of lines that shine with life.

Derek Walcott

da “The Bounty: Poems”, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1998