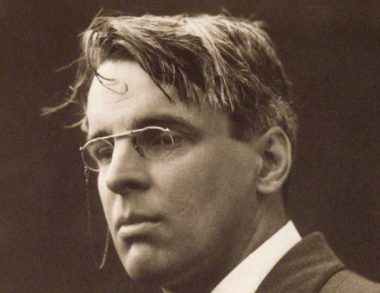

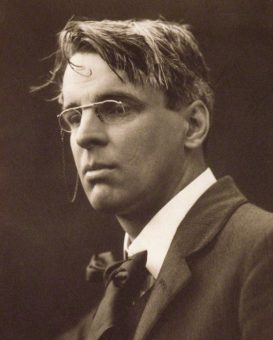

George Charles Beresford, William Butler Yeats, 1911

Hic

Sulla sabbia grigia, lungo il ruscello,

sotto la tua vecchia torre battuta dai venti

dove ancora arde un lume accanto al libro

che lasciò aperto Michael Robartes,

tu cammini sotto la luna e pure se i tuoi anni migliori

sono trascorsi, ancora cedi al fascino

di invincibili illusioni e tracci forme magiche.

Ille

Con l’aiuto di un’immagine

evoco il mio opposto, invoco tutto ciò

che meno ho guardato, ciò che meno ho curato.

Hic

Me stesso, non un’immagine io vorrei trovare.

Ille

È questa la speranza dei moderni, e alla sua luce

abbiam trovato la mente mite, sensibile

perdendo l’antica scioltezza della mano;

e non conta che usi scalpello, penna o pennello.

Siamo solo critici, creatori solo a metà,

timidi, confusi, vuoti e imbarazzati,

senza il sostegno dei nostri compagni.

Hic

Eppure Dante Alighieri, la mente

più immaginativa della Cristianità,

trovò se stesso, tanto che all’occhio della mente

il suo volto scavato è più espressivo

di ogni altro volto, tranne quello di Cristo.

Ille

Ma trovò se stesso,

o fu la bramosia a scavargli il volto,

il desiderio della mela che è sul ramo

più alto? E quell’immagine spettrale

fu l’uomo a Lapo e Guido amico?

Credo che lui l’abbia plasmata sul suo opposto,

forse l’immagine di un volto di pietra

che da una casa scavata nella roccia

fissa lo sguardo su un tetto beduino di crine di cavallo,

o è mezzo rovesciato fra sterco di cammello ed erba incolta.

Col suo scalpello lavorò alla pietra più dura.

Deriso da Guido per la sua vita lasciva,

beffardo e beffato, esiliato e costretto

a salir le scale altrui a mangiare pane amaro,

egli trovò una giustizia incorruttibile, e la più nobile

fra le donne che mai furono amate.

Hic

Eppure c’è di certo un’arte

che non nasce da tragici conflitti ma da uomini

amanti della vita, che si gettano a cercare la felicità

e cantano quando l’hanno trovata.

Ille

No, non cantano,

perché chi ama il mondo lo serve con l’azione,

diventa ricco, celebre, influente

e se scrive o dipinge sempre agisce:

la lotta della mosca nella marmellata.

Il retore vuole ingannare che gli è accanto,

il sentimentale se stesso; l’arte invece

non è che una visione del reale.

Qual è la parte nel mondo per l’artista

una volta desto dal sogno comune?

Solo disperazione e dispersione.

Hic

Eppure

nessuno nega che Keats amasse il mondo;

rammenta la sua deliberata felicità.

Ille

La sua arte è felice, ma chi può scrutargli la mente?

Io vedo uno scolaro quando penso a lui,

il viso e il naso schiacciati contro una vetrina

di dolciumi; di certo egli scese nel sepolcro

con il cuore e i sensi insoddisfatti

e compose − povero, afflitto e incolto,

escluso dalle ricchezze del mondo,

rude figlio di un custode di cavalli −

ricchi canti.

Hic

Perché lasci che il lume

arda da solo accanto al libro aperto

e tracci questi segni sulla sabbia?

Lo stile va cercato con un duro lavoro

sedentario e imitando i grandi del passato.

Ille

Perché è un’immagine che cerco, non un libro.

Gli uomini che nei loro scritti son più saggi

possiedono solo cuori ciechi, intorpiditi.

Evoco la creatura misteriosa che verrà lungo il ruscello

sulla sabbia umida; sarà simile a me,

poiché è il mio doppio,

e di tutte le cose immaginabili la più dissimile

si rivelerà, perché è il mio anti-sé;

eretto in mezzo a questi segni svelerà

ciò che io cerco. E lo sussurrerà,

come se timoroso che gli uccelli, prima dell’alba

lanciano in cielo i loro brevi gridi,

lo portino ai blasfemi.

William Butler Yeats

Dicembre 1915

(Traduzione di Gino Scatasta)

da “Per amica silentia lunae”, Il cavaliere azzurro, Bologna, 1986

Scritta nel 1915, questa poesia fu pubblicata nel 1917 sulla rivista «Poetry » e in seguito, nel 1919, nella raccolta The Wild Swans at Coole. Il titolo è tratto dalla Vita Nova dantesca. Per un esauriente commento alla poesia, si vedano le note di Anthony L. Johnson in W.B. Yeats, L’opera poetica, Mondadori, Milano 2008, pp. 1199-1205.

Michael Robartes compare per la prima volta nel racconto Rosa Alchemica, scritto nel 1897. È un occultista, fondatore di un ordine esoterico, e simboleggia per Yeats una personalità soggettiva, antitetica. Robartes riappare nelle poesie di The Wind among the Reeds (1899), in The Double Vision of Michael Robartes (1919) e nel titolo della raccolta di poesie del 1921 Michael Robartes and the Dancer. In A Vision (I ed. 1925, II ed. 1937), Robartes compare nella poesia introduttiva, The Phases of the Moon, dove insieme ad Aherne (altra maschera di Yeats, il sé oggettivo) passa sotto la torre del poeta e spiega all’amico le fasi della luna, le ventotto possibili personalità umane, che non potranno essere mai comprese dal poeta che studia libri e manoscritti alla luce di una lampada.

Sempre in A Vision, in Le storie di Michael Robartes e dei suoi amici, Michael Robartes riappare come un uomo «magro, bruno, muscoloso, perfettamente sbarbato, con lo sguardo vivo e ironico ». È a capo di una setta mistica, della quale fa parte anche il suo amico Aherne, che ha come scopo la rigenerazione del mondo. (Cfr. W.B. Yeats, Una visione, trad. it. di Adriana Motti, Adelphi, Milano 1973.)

∗∗∗

Ego dominus tuus

Hic

On the grey sand beside the shallow stream,

Under your old wind-beaten tower, where still

A lamp burns on above the open book

That Michael Robartes left, you walk in the moon,

And, though you have passed the best of life, still trace,

Enthralled by the unconquerable delusion,

Magical shapes.

Ille

By the help of an image

I call to my own opposite, summon all

That I have handled least, least looked upon.

Hic

And I would find myself and not an image.

Ille

That is our modern hope, and by its light

We have lit upon the gentle, sensitive mind

And lost the old nonchalance of the hand;

Whether we have chosen chisel, pen, or brush,

We are but critics, or but half create,

Timid, entangled, empty, and abashed,

Lacking the countenance of our friends.

Hic

And yet,

The chief imagination of Christendom,

Dante Alighieri, so utterly found himself,

That he has made that hollow face of his

More plain to the mind’s eye than any face

But that of Christ.

Ille

And did he find himself,

Or was the hunger that had made it hollow

A hunger for the apple on the bough

Most out of reach? And is that spectral image

The man that Lapo and that Guido knew?

I think he fashioned from his opposite

An image that might have been a stony face,

Staring upon a Beduin’s horse-hair roof,

From doored and windowed cliff, or half upturned

Among the coarse grass and the camel dung.

He set his chisel to the hardest stone;

Being mocked by Guido for his lecherous life,

Derided and deriding, driven out

To climb that stair and eat that bitter bread,

He found the unpersuadable justice, he found

The most exalted lady loved by a man.

Hic

Yet surely there are men who have made their art

Out of no tragic war; lovers of life,

Impulsive men, that look for happiness,

And sing when they have found it.

Ille

No, not sing,

For those that love the world serve it in action,

Grow rich, popular, and full of influence;

And should they paint or write still is it action,

The struggle of the fly in marmalade.

The rhetorician would deceive his neighbours,

The sentimentalist himself; while art

Is but a vision of reality.

What portion in the world can the artist have,

Who has awakened from the common dream,

But dissipation and despair?

Hic

And yet,

No one denies to Keats love of the world,

Remember his deliberate happiness.

Ille

His art is happy, but who knows his mind?

I see a schoolboy, when I think of him,

With face and nose pressed to a sweetshop window,

For certainly he sank into his grave,

His senses and his heart unsatisfied;

And made − being poor, ailing and ignorant,

Shut out from all the luxury of the world,

The ill-bred son of a livery stable keeper −

Luxuriant song.

Hic

Why should you leave the lamp

Burning alone beside an open book,

And trace these characters upon the sand?

A style is found by sedentary toil,

And by the imitation of great masters.

Ille

Because I seek an image, not a book;

Those men that in their writings are most wise

Own nothing but their blind, stupefied hearts.

I call to the mysterious one who yet

Shall walk the wet sand by the water’s edge,

And look most like me, being indeed my double,

And prove of all imaginable things

The most unlike, being my anti-self,

And, standing by these characters, disclose

All that I seek; and whisper it as though

He were afraid the birds, who cry aloud

Their momentary cries before it is dawn,

Would carry it away to blasphemous men.

William Butler Yeats

December 1915.

da “Per Amica Silentia Lunae”, Macmillan, 1918